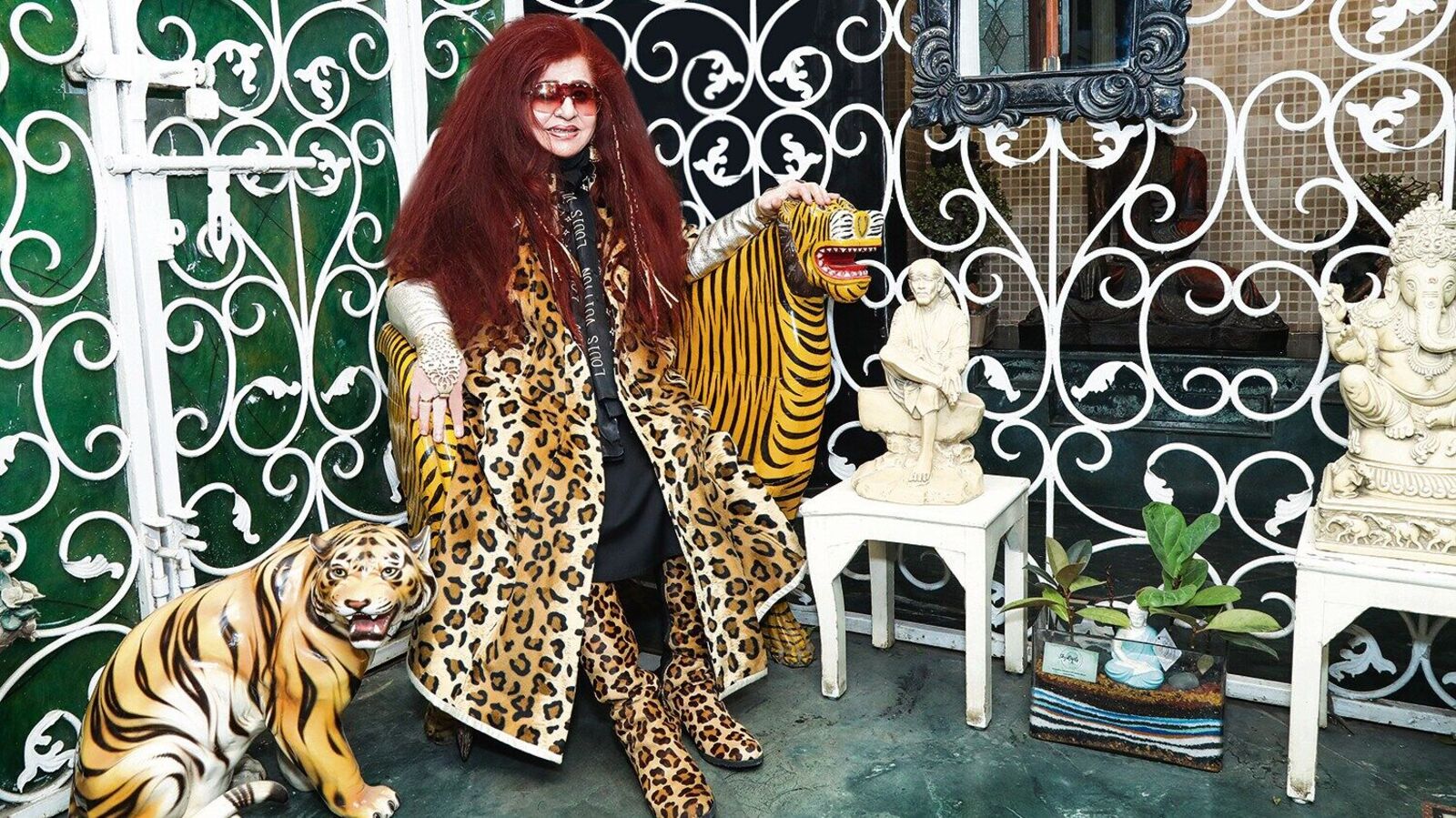

It is difficult to forget her. She doesn’t look like she’s aged a day since I first saw her in the lobby of Delhi’s Oberoi hotel 20 years ago. With her henna-coloured billowy hair, pea-sized diamond nose pin and peach-red lipstick, she’s the original beauty influencer who started a herbal cosmetics revolution in India in the 1970s by putting kitchen remedies in plastic jars and her face and name on the label.

When we meet, she’s dressed in an electric-blue kurta-shirt with matching pants, a long black jacket, pale-gold leather gloves with cut-out detailing to reveal just her red nails, and a bright blue scarf with multi-coloured LV logos. Her kohl-lined eyes are hidden behind Louis Vuitton sunglasses. “You know, I am here because of you,” she says while settling into a chair that resembles a golden throne. She’s referring to the press. “If you guys had not written about me all these years, I would have not reached here.”

Since starting her eponymous brand in 1971, Husain, who turns 81 this year, has built a business selling 5,000-year-old Ayurvedic formulations in modern packaging well before terms like “clean beauty” and “organic beauty” were conceived. At present, the brand, which is also managed by her daughter Nelofar Currimbhoy, has over 150,000 stores across 138 countries. They sell 300 formulations, some with 24-carat gold, oxygen, pearl and plant stem cells. It recently launched Marrdd, a skincare line for men. While Husain refuses to talk numbers, estimates put “her peak revenues at about $375 million”, according to a 2024 Mint report.

The journey started with her learning the basics of cosmetics at a beauty school in Delhi’s Defence Colony. She was 15, newly married and bored. “I wasn’t really interested in beauty, but my father (Nasir Ullah Beg, former chief justice of the Allahabad high court) used to encourage me to read a lot. I came across several reports in newspapers stating that people had died after getting their hair coloured, or that their skin had burnt because they used some chemical cream. It made me wonder why people weren’t using traditional herbs and nuskhe (remedies), stuff we all grew up with at home,” she says. Her own haircare routine has always consisted of henna and a strict weekly routine of “13 eggs, coffee, lime juice” as hair pack.

Soon she, along with her one-year-old daughter, moved to Tehran with her husband Nasir Husain, who was then director for foreign trade at State Trading Corporation. Her interest in beauty had grown, and she wanted to do cosmetology courses, but didn’t want to borrow money from her father or husband. So, she started writing articles in an English language newspaper in Iran to eventually fund her education at leading schools in the UK, Germany and the US.

Her decision to promote the use of herbs as skincare in a world of chemicals took shape during the early days at Helena Rubinstein School of Beauty in the 1960s in London, when she learnt about an accident from a classmate-turned-friend. “Her mother had been a model for a make-up company and her eyes had started blurring after using some products and eventually she lost her eyesight and became blind,” she recalls. “That was the point that decided my future. I told myself I am going to study all the chemical formulas, and then recreate them using plants in India.”

Back in Delhi in 1971, Husain set up a factory in Okhla. She started creating solutions for dullness, hair fall, acne, stretch marks, dark circles and pigmentation and selling them from her first herbal salon in the veranda of her home. The products were an instant success. She was also setting up salons for housewives to get trained in beauty techniques and earn a living.

Over the next seven years, Husain represented India at international fairs, including the prestigious New York Beauty Congress. In 1982, she became the first Asian woman to retail her products from British store Selfridges. Soon, she was in Harrods (UK), La Rinascente (Italy), El Corte Inglis (Spain), Bloomingdales (US), Japan’s Seibu chain and Galleries Lafayette (France). Newspapers and magazines across the world hailed her as the “Ayurveda queen from India”. Socialites as well as Hollywood stars wanted her products, especially the saffron-infused skin brightening cream. Shahnaz bridal glow treatment became a must have for brides-to-be.

Competition started building two decades ago, with the emergence of premium Ayurveda-focused skincare brands like Kama Ayurveda and Forest Essentials. Husain wasn’t too bothered. “I was too consumed with what I was building; I am still like that,” she says.

In the past decade, she’s launched products like a castor oil-infused Touch-Up in a big lipstick-like bottle to conceal grey hair instantly and gel-like eye mask packed with seaweed (known for its hydrating properties). Despite the new generation of beauty entrepreneurs, Husain continues to hold sway among loyalists who swear by her kajal, henna, all-season face cream and face mask with diamond dust—more so because of the price point that falls in the ₹200-2,000 range.

At present, her focus is on Marrdd, which offers the usual creams, scrubs, shaving cream, hair oil and tonic for men. The other thing keeping her busy is expansion. She doesn’t get into specifics but says she is launching more stores this year.

A large part of her success has come from her in-your-face marketing strategy. Even today, Shahnaz Husain has no influencer-led brand promotions or brand ambassadors. “I am Shahnaz Husain the brand; the brand is me,” she says. “I was selling an ancient science when hardly anyone was talking about it and look around you now, everyone is doing what I was doing 50 years ago. There’s no competition. I am going to stick to what I know.”

I ask her what she does when she’s not working. “Wait,” she says, excitedly. She calls one of her assistants on the phone and 10 minutes later, 20 long coats are paraded in front of me. Some have leopard print on the collars, sleeves and shoulders; there’s a peplum-style burgundy overcoat with fuchsia pink lining and gold buttons; another has the LV logo embossed all over barring the sleeves. “I shop for bags, shawls and scarfs, cut them up and make my own clothes,” she says, adding proudly that her outfit of the day is also her own design. She has four in-house tailors. “I don’t wear designer clothes, everything from top to bottom is bespoke. I always wanted to start a fashion label.”

Then what stopped you? “That’s a story for the next interview.”