Making exercise fun is the holy grail for many people who can’t quite find the motivation to work out.

But rather than forcing yourself to enjoy running or that gym class you once attended, the solution may lie in something more straightforward — simply matching a workout to your personality type, according to a study published Tuesday in the journal Frontiers in Psychology.

That’s because people with different personality traits enjoy different types of exercise, the study found.

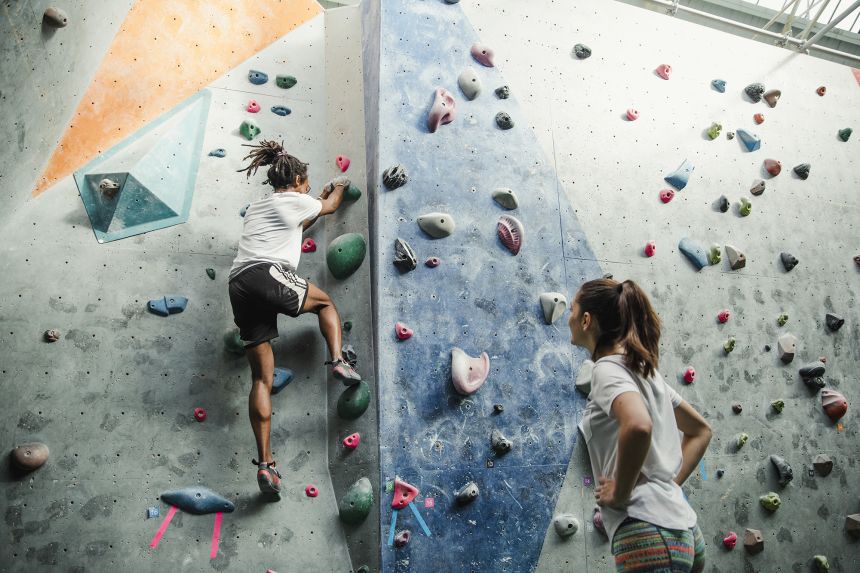

More extroverted people, for example, prefer high-intensity training sessions with others, such as team sports, while people who scored highly on “neuroticism,” a metric that measures someone’s emotional instability, preferred private workouts without people watching them and punctuated by short breaks.

As for those who scored highly on conscientiousness, they “were more likely to have a well-rounded fitness … and we think that’s because conscientious individuals are more likely to be driven by the fact that exercise is good for them,” said the study’s co-lead author, Flaminia Ronca, an associate professor in exercise science at University College London.

“Personality determines which intensities and forms of exercises we’re attracted to. … If we can understand that, then we can make that first step in engagement and exercise in sedentary individuals,” she told CNN.

These findings have important implications for encouraging more people to exercise, especially since just 22.5% of adults and 19% of adolescents worldwide manage the World Health Organization-recommended 150 minutes of physical activity per week, according to the study.

By focusing on personality types, health care providers may be able to offer a “more personalized approach to exercise,” said Angelina Sutin, a professor at Florida State University who specializes in investigating links between personality and health, and who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Typically … we tell people to exercise and just say: ‘We know high-intensity interval training is good for you, so you should do it,’” she said.

“But for people high in neuroticism, they’re not going to do it, and we also know that low-intensity exercise can be beneficial too. Knowing that somebody is high in neuroticism, recommending that kind of exercise, maybe people will be more likely to engage in it.”

It is also important to note that personality traits interact with each other, Ronca added. Some people score highly on both neuroticism and conscientiousness, meaning that although they may find exercise anxiety-inducing, they are much more likely to do it since they know it is good for them, she said.

To reach their findings, Ronca and her colleagues in London first directed the 132 study participants, aged between 25 and 51 years old, to complete a questionnaire revealing their personality traits.

The study employed a commonly used model that conceptualizes someone’s personality through five traits — extroversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, openness and conscientiousness.

“Personality traits … they’re just descriptions of the way people behave in certain situations,” Paul Burgess, a professor of neuroscience at UCL who co-led the study, told CNN.

“And the way that people behave in certain situations is determined to a large degree by their brain capabilities, what they notice, what they pay attention to, what they can remember, how fast they can react.”

The researchers then ran fitness tests on the participants and randomly sorted them into two groups. One group was given an eight-week cycling and strength plan, while the control group did 10 minutes a week of stretching exercises. Of the original 132 participants, 86 completed both pre- and post-testing either side of these eight weeks.

The study team found that, although fitness improved across all personality types for those who completed the cycling and strength program, there was a marked difference in enjoyment of the exercises. More extroverted people enjoyed the higher-intensity lab fitness tests, while more “neurotic” people enjoyed the home-based light-intensity sessions.

Personality traits also informed how exercise influenced someone’s stress levels. People who scored highly in neuroticism had a significant reduction in self-reported stress, much more than in any other group, the study found.

“Those who would benefit the most from a stress reduction are the ones who actually showed a decrease in stress following those eight weeks of exercise,” Ronca said. “And I think that’s quite a powerful message to give.”

Given the many benefits of exercise, including stress reduction, both Ronca and Burgess hope their findings encourage people to find alternative ways of exercise outside the more traditional workouts they might dislike.

“There’s a danger, perhaps, that the focus becomes … competitive sports and serious engagement at a time when young people are starting to have lots more demands on them,” Burgess said.

“There are a lot of personalities that don’t respond well to that kind of situation, that find it quite stressful.”

Sign up for CNN’s Fitness, But Better newsletter series. Our seven-part guide will help you ease into a healthy routine, backed by experts.