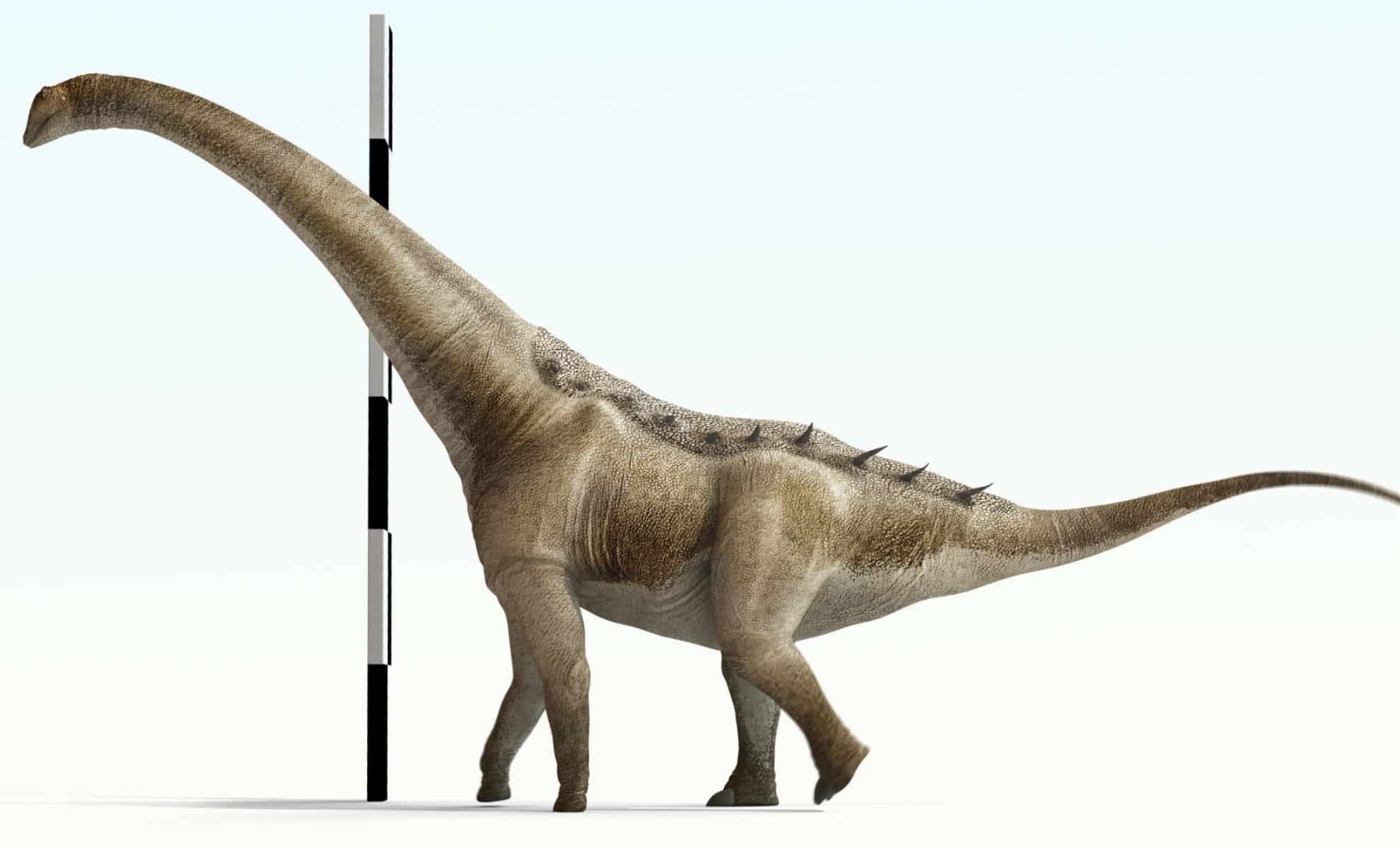

A newly described species of titanosaurian dinosaur has just been unearthed in central Spain, and it’s revealing a previously hidden chapter in the story of Late Cretaceous Europe. The dinosaur, named Qunkasaura pintiquiniestra, was discovered at the fossil-rich site of Lo Hueco in Cuenca, and it represents one of the most complete sauropod skeletons ever found in Europe. The findings, published in the journal Communications Biology, suggest that Europe, during the final chapters of the dinosaur era, was more of a biological crossroads than previously believed.

With its distinct anatomy and unexpected ancestry, Qunkasaura may be proof that sauropod dinosaurs from multiple continents converged in what was once a sprawling island chain covering the Iberian Peninsula.

A Successful Lineage That Left a Massive Legacy

Qunkasaura pintiquiniestra belonged to Titanosauria, a diverse and globally widespread group of long-necked sauropods. This clade not only flourished during the Mesozoic but also achieved extraordinary levels of evolutionary success.

“Titanosauria was a successful group of sauropod dinosaurs that experienced an important event of diversification in the Early Cretaceous, with the establishment of several distinct lineages including Lithostrotia,” said University of Lisbon’s Dr. Pedro Mocho and his colleagues.

Within Lithostrotia, titanosaurs ranged dramatically in size and shape, from small island dwellers to the largest animals to ever walk the Earth.

“Lithostrotians dominated the Late Cretaceous sauropod fauna and were represented by two main groups, the saltasauroids, and colossosaurs, including from small forms to the largest known land animals.”

“They survived until the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, when they became extinct as all other non-avian dinosaurs.”

Qunkasaura’s arrival in the Iberian fossil record suggests it was part of a previously unknown lineage of these titanic reptiles, distinct from the smaller sauropods typically associated with Europe’s ancient island ecosystems.

A Fossil With Exceptional Preservation

The partial skeleton of Qunkasaura includes neck, back, and tail vertebrae, along with parts of the pelvis and limbs. This level of preservation is exceptionally rare in European sauropods, offering paleontologists one of their clearest views yet into the anatomy of Iberian titanosaurs.

“Qunkasaura pintiquiniestra stands out for being one of the most complete sauropod skeletons found in Europe, including cervical, dorsal and caudal vertebrae, part of the pelvic girdle and elements of the limbs,” they said.

“Their unique morphology, especially in the tail vertebrae, offers new insights into the non-avian dinosaurs of the Iberian Peninsula, a historically poorly understood group.”

The fossil’s anatomy, particularly in the tail, has enabled researchers to make detailed comparisons with other titanosaur groups, placing Qunkasaura in a surprising evolutionary branch.

A New Contender in an Old Island World

While many Iberian titanosaurs are known to have evolved in isolation, shaped by Europe’s island geography in the Late Cretaceous, Qunkasaura appears to come from an entirely different evolutionary path.

“One of these groups, called Lirainosaurinae, is relatively well known in the Iberian region and is characterized by small and medium-sized species, which evolved in an island ecosystem,” Dr. Mocho said.

“In other words, Europe was a huge archipelago made up of several islands during the Late Cretaceous.”

But Qunkasaura doesn’t fit that insular profile. Instead, it appears to belong to a group of larger-bodied sauropods, which may have arrived in the region long after the Lirainosaurines were already well-established.

“However, Qunkasaura pintiquiniestra belongs to another group of sauropods, represented in the Iberian Peninsula by medium-large species around 73 million years ago.”

“This suggests to us that this lineage arrived in the Iberian Peninsula much later than other groups of dinosaurs.”

A Migrant From the North?

The evolutionary roots of Qunkasaura point toward an origin far from the Mediterranean. The dinosaur belongs to the opisthocoelicaudine saltasaurids, a group better known from the northern hemisphere, rather than the endemic species commonly found in southern Europe.

“We identify Qunkasaura pintiquiniestra as a representative of the opisthocoelicaudine saltasaurids, a group present in the northern hemisphere (Laurasia),” the researchers said.

Its presence at Lo Hueco suggests a wave of sauropod immigration into the Iberian Peninsula late in the Cretaceous, possibly via shifting land bridges or changing sea levels.

As paleontologists continue to study the fossils from this site, Qunkasaura is fast becoming more than just a new species—it’s a vital clue to understanding how dinosaurs spread across ancient, fragmented continents, and how the final chapters of the Age of Dinosaurs unfolded in Europe’s prehistoric island world.