On April 2, in a Rose Garden ceremony, US President Donald Trump will declare “Liberation Day.” But instead of freeing the economy, the tariffs he plans to unveil could slam the brakes on global growth, ignite inflation, and throw the world into an economic tailspin.

Driving the news

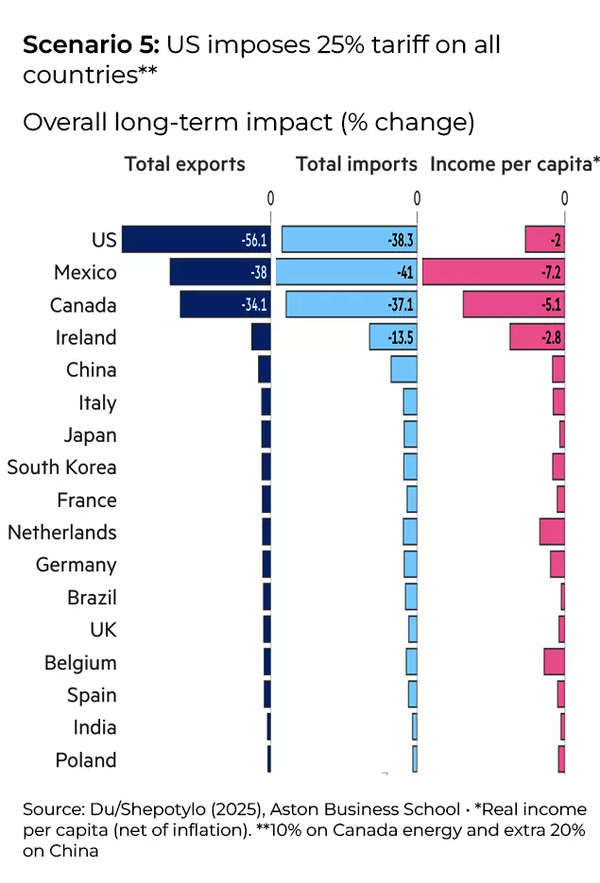

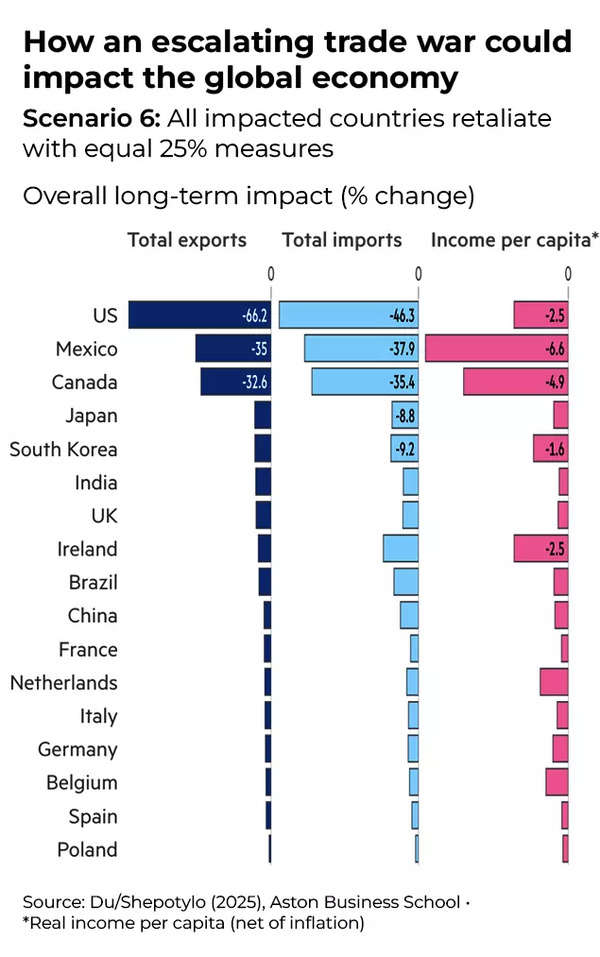

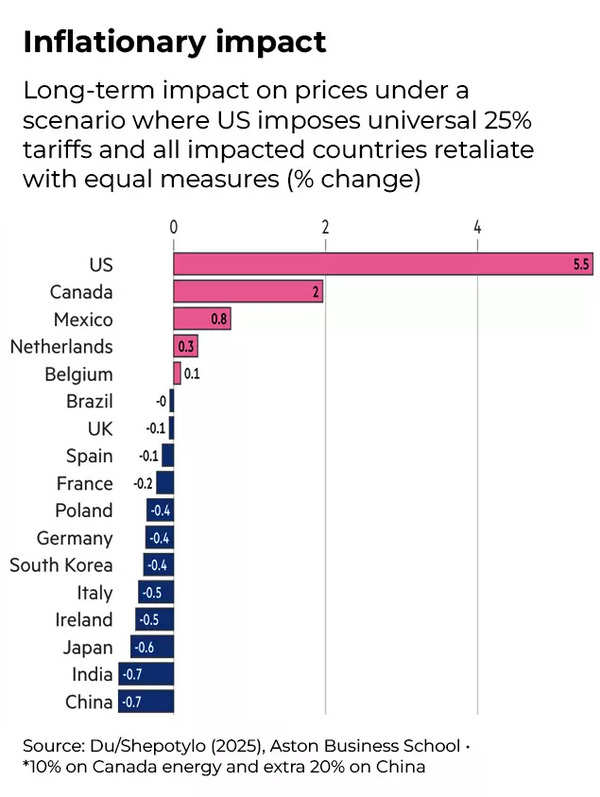

- According to a Financial Times report that is based on econometric study by Aston University, a worst-case global retaliation to Trump’s proposed 25% tariffs could hammer the world economy with a $1.4 trillion income hit and cripple global trade.

- The research models six escalating scenarios based on bilateral trade data from 132 countries, showing how a tit-for-tat tariff spiral would move from North America to Europe and beyond — destabilizing supply chains and inflating prices.

- As per a Washington Post report, White House adviser Peter Navarro said Sunday that President Donald Trump’s new tariffs would generate more than $6 trillion in federal revenue over the next ten years — a projection that, if realized, would amount to the largest peacetime tax increase in modern US history, according to experts.

- Speaking on Fox News, Navarro said the tariffs on auto imports would bring in $100 billion annually. He added that a broader set of still-unspecified tariffs would yield an additional $600 billion per year, totaling $6 trillion over the next decade.

Why it matters

- Trump’s advisers argue the economic pain is worth it. They envision a future where American factories hum again, imports shrink, and tariff revenue funds a new era of domestic tax cuts.

- “Access to cheap goods is not the essence of the American Dream,” said treasury secretary Scott Bessent. “The dream is rooted in upward mobility and economic security.”

- But investors and economists aren’t convinced. The S&P 500 dropped 4.6% in Q1, its worst start since 2022.

- Goldman Sachs increased the probability of a US recession to 35%, up from 20%.

- US allies, including Canada, Japan, and Germany, have warned the White House that indiscriminate tariffs could spark retaliatory spirals and damage global growth.

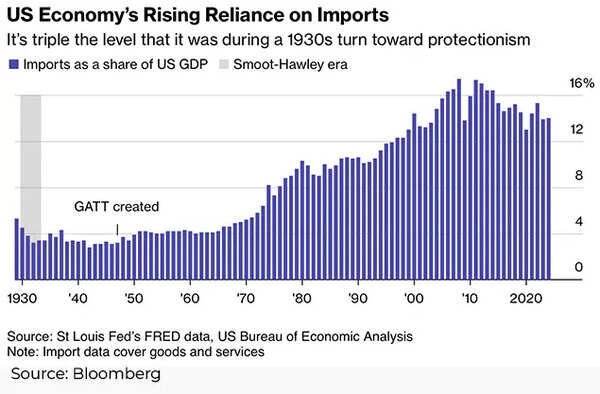

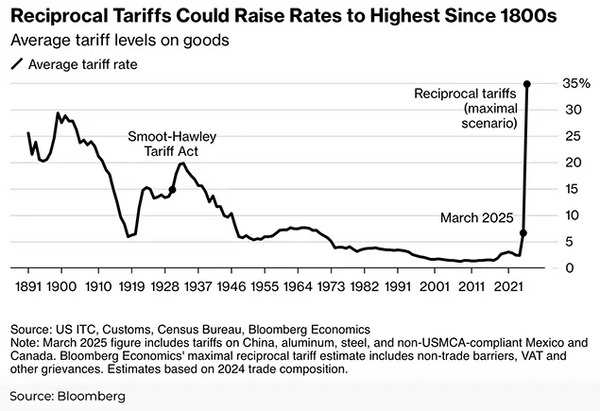

- “This is going to be much bigger than Smoot-Hawley,” said economic historian Douglas Irwin. “Imports are a much greater share of GDP now than they were in the early 1930s.”

We’re going to charge countries for doing business in our country and taking our jobs, taking our wealth, taking a lot of things that they’ve been taking over the years. They’ve taken so much out of our country, friend and foe.

Donald Trump

Trump’s plan — targeting countries that impose higher tariffs on US goods — could significantly reshape the global economic order. According to the FT report, the research conducted by economists at Aston University explores how a cycle of retaliatory tariffs triggers intricate changes in global trade, initially impacting North America—specifically the US, Mexico, and Canada—before extending to Europe and eventually affecting the rest of the world.

While a few nations like India may reap modest gains from diverted trade, the bigger picture is grim:

- US exports fall over 46%, triggering steep domestic inflation of more than 5%.

- Living standards decline globally, especially in countries heavily dependent on US trade.

- Bloomberg Economics estimates US GDP could shrink by 4% if tariffs are widely imposed and retaliated. Prices could jump 2.5% over 2–3 years, hurting consumer purchasing power.

- India, the UK, Japan, and South Korea could benefit temporarily — but only if escalation remains moderate.

India’s strategic opportunity—and its limits

India appears, on paper, to be one of the few countries with something to gain. In scenarios where trade patterns shift to avoid US-EU or US-China tariff barriers, India, along with the UK, Japan, and South Korea, could benefit modestly from trade diversion. These countries might see increased demand for exports in sectors where the US previously relied on more tariff-encumbered suppliers.

For India, the opportunity lies in electronics, pharmaceuticals, and textiles—sectors already being nurtured under the “Make in India” initiative. The country’s growing reputation as a manufacturing alternative to China, along with a neutral position outside major trade blocs like the EU, could position it as a go-to supplier in a time of uncertainty.

But the gains are marginal. And fleeting.

“India might benefit from a few supply chain shifts,” said a senior economist at a New Delhi-based think tank, “but if the global trade environment turns volatile, capital flows will become unstable, inflation will rise, and the ripple effects will catch up.”

Indeed, India imports much of its energy, machinery, and high-end components. A broad-based trade war would make many of these imports more expensive. That would stoke inflation and squeeze the government’s fiscal room. The Reserve Bank of India, already cautious due to sticky food prices, might be forced to tighten policy—potentially dampening growth.

In short: India might catch a breeze in the early gusts, but it won’t escape the storm.

Back to the future?

Interestingly, Trump’s renewed tariff push comes at a time when the US economy is more reliant on imports than ever before. Its imports now account for roughly 14–16% of US GDP — a figure nearly triple what it was during the protectionist Smoot-Hawley era of the 1930s. This underscores how deeply integrated the US is in global supply chains today. A return to aggressive tariffs, like those Trump is proposing, risks shocking a system built on decades of liberalized trade policy, a Bloomberg report said.

Next, if fully implemented, his “reciprocal tariff” strategy would drive US average tariff levels on goods up to around 35%—the highest since the late 1800s. This would far surpass even the levels seen during the infamous Smoot-Hawley period, which historians widely blame for deepening the Great Depression. Trump’s plan would reintroduce trade barriers at a scale unseen in over a century, despite a modern economy far more exposed to international commerce.

The contrast between the two charts paints a stark picture: while the structure of the US economy has evolved to depend heavily on imports, Trump’s proposed trade policy appears rooted in an era when international trade was minimal. Economists warn this disconnect could fuel inflation, disrupt industries, and lead to retaliation that hobbles both global and domestic growth.

What’s next?

Trump’s long-promised “Liberation Day” speech will be watched for three key details:

Universal or reciprocal? The White House remains split.

Sectoral carveouts? Automobiles, steel, pharma, and semiconductors are in focus.

Duration and flexibility. Will tariffs be negotiable or fixed for the long term?

Inside the West Wing, factions are pushing different approaches. Some advocate a hard 20% universal tariff to send a signal. Others want a flexible structure to open room for bilateral negotiations.

“With Trump, it’s all a negotiation,” said Sen. James Lankford. “This is like a kitchen remodel. It’s going to be noisy, but we know where we’re headed.”

But others warn, “You don’t remodel the global economy with a hammer,” a European trade official quipped off record.

The bottom line

Trump’s tariff plan is a bold gamble that could remake the global trading system — or plunge it into prolonged uncertainty. India finds itself in a rare position: not the target of the first strike, and possibly in line for modest trade gains.

But as history warns, and the data confirms, no country is truly safe when tariffs become the world’s economic weapon of choice.